Raif Badawi, a Saudi Arabian journalist and founder of the Liberal Saudi Network, was arrested in 2012 by the Saudi government and sentenced in a grossly unjust trial, based on charges stemming solely from him establishing an online debate forum. He was accused of “insulting Islam through electronic channels” and “going beyond the realm of obedience.” In 2013 Badawi was cleared of an apostasy charge, which could have carried a death sentence; still, his ultimate sentence was ten-years imprisonment, a fine of a million Saudi riyals (more than $266,000), and a “flogging” of 1,000 lashes. The first of these floggings took place January 9, 2015.

Raif Badawi, a Saudi Arabian journalist and founder of the Liberal Saudi Network, was arrested in 2012 by the Saudi government and sentenced in a grossly unjust trial, based on charges stemming solely from him establishing an online debate forum. He was accused of “insulting Islam through electronic channels” and “going beyond the realm of obedience.” In 2013 Badawi was cleared of an apostasy charge, which could have carried a death sentence; still, his ultimate sentence was ten-years imprisonment, a fine of a million Saudi riyals (more than $266,000), and a “flogging” of 1,000 lashes. The first of these floggings took place January 9, 2015.

Along with amputations and beheadings, such public floggings have been common in the Kingdom since its founding in 1932. The day after Badawi’s flogging, eight U.S. senators wrote a letter to Saudi King Abdullah, urging “the immediate halt to this barbaric punishment and the immediate release of Mr. Badawi.” King Abdullah died just two weeks later and one of his brothers, Salman bin Abdulaziz, ascended to the Crown.[1]

After I made the photos, I wrestled with what to do with them. None of the major human rights organizations I contacted, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Pen International, nor global press outlets such as Reuters or France 24, were willing to publish my photos under terms to protect my anonymity. This was perhaps also out of concern that Badawi would face some repercussions while imprisoned. I could have also reached out to other press outlets, but the reluctant response I received made me hesitant to proceed in the photos’ release.

In March, 2022, Badawi was released from prison after completing his sentence, yet still faces an onerous travel ban which prevents him from seeing his wife and children for another decade. In consultation with some key human rights organizations, I have decided that now, since his release from prison, the promulgation of the photos should no longer be delayed.

The following are edited excerpts of an interview I made in 2019 with filmmaker Luc Côté for his documentary film, “Waiting for Raif.”

Elliott – “It’s been a number of years since I experienced the flogging of Raif Badawi, but I remember it very vividly. I was working in Saudi Arabia as Press Attaché for the U.S. Consulate in Jeddah for some six months, and was privy to the news that this journalist was scheduled to be publicly flogged. It was Friday, the first day of our weekend. I knew that Badawi had been sentenced to receive a thousand lashings and I recognized the significance of documenting the abuse, should it take place. There was some doubt whether the lashing would actually occur, since the Saudi government was secretive.

“On my own time, I was driven downtown by a Saudi friend. I was deposited near the mosque, Masjid Al-Jaffali, where the punishment was to be meted out. I immediately noticed a lot of men and boys walking in the direction of the mosque.

“On my own time, I was driven downtown by a Saudi friend. I was deposited near the mosque, Masjid Al-Jaffali, where the punishment was to be meted out. I immediately noticed a lot of men and boys walking in the direction of the mosque.

“I started walking with the people and after a few blocks we numbered hundreds of people. We arrived to a parking lot for the Masjid, and at first [it seemed like] foot traffic for a normal Friday Jummah prayers. I observed everyone following the instructions to pray both inside and outside of the mosque; the prostrating and standing sequence continued for some 15 minutes.

“I started walking with the people and after a few blocks we numbered hundreds of people. We arrived to a parking lot for the Masjid, and at first [it seemed like] foot traffic for a normal Friday Jummah prayers. I observed everyone following the instructions to pray both inside and outside of the mosque; the prostrating and standing sequence continued for some 15 minutes.

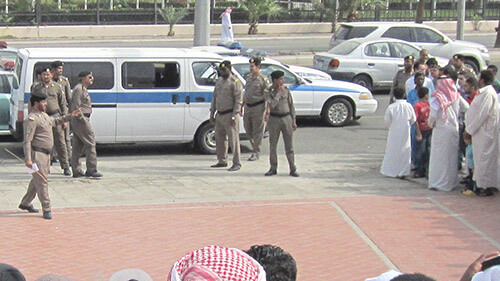

“When the prayers were completed, I walked with most of the congregants to a wide stairway [in front of the mosque]. I stood behind a few rows of men from this vantage point. About this time, I started hearing announcements in Hijazi Arabic via the public address speakers. A group of policemen [officers of the Saudi Arabian National Guard] were scanning the crowd. The Saudi Ministry of Information building was prominent in the background. I wasn’t sure exactly what they were ordering them to do, but after a few minutes I noticed that they were confiscating mobile phones.

“When the prayers were completed, I walked with most of the congregants to a wide stairway [in front of the mosque]. I stood behind a few rows of men from this vantage point. About this time, I started hearing announcements in Hijazi Arabic via the public address speakers. A group of policemen [officers of the Saudi Arabian National Guard] were scanning the crowd. The Saudi Ministry of Information building was prominent in the background. I wasn’t sure exactly what they were ordering them to do, but after a few minutes I noticed that they were confiscating mobile phones.

[Listening to audio recording*] “What you’re hearing is the warning announcements of the police over the PA system. [At 03:40] They say “Nothing is allowed to be recorded. It is not permitted to record using any video or audio equipment. Put away your cameras or we will take them away.” I understood Arabic, but the voice was distorted, so I didn’t realize at the time this direct admonition.

“I didn’t have a mobile phone but I did have a small [Canon] camera I always kept on me for my official work. I planned to take one quick picture, and positioned myself between two men, after setting the camera to a 35mm lensing. I very slowly raised the device so it just cleared the shoulders of the men; I could not actually look through the viewfinder.

“This is the first photo, before Badawi appeared. I then slowly lowered the camera. I saw on my watch that it was almost 1p.m. The doors to the van rolled open and a somewhat scrawny man was brought out, hands out front, shackled. He also looked very sleepy and sheepish, but I recognized a gaunt Raif Badawi and I estimated his weight at around 120 lbs.

“A policeman stood by, [with] a long cane in his hand. This cane was about two foot long, a bit thicker than the diameter of a pencil, and looked to be made of bamboo. (You can buy them in the souks anywhere in the country; perhaps parents use them to punish their children.) I noticed that Badawi was made to face toward Mecca, the direction in which everybody else had just prayed. Meanwhile, the police officers were still looking vigilantly at these 400 or so people assembled around, to make sure nobody took any videotaping or with mobile phones. There was a hushed and tense apprehension. One officer might have seen me, but because my camera was black and very small and I raised it up very slowly like a turtle, he didn’t notice me.

“An officer then began whipping Badawi very hard. I was a little bit surprised that they kept Badawi’s shirt on, and at first, he didn’t seem to be visibly affected by the blows, until I noticed he increasingly flinched and shoulders rose somewhat after each strike. I dared to raise my camera once again, around the 20th blow.

“I noticed toward the end of the allotted number that he was flinching significantly. I felt a surge of empathy with him and was quite shocked and horrified by this anachronistic spectacle. At the 50th blow, Badawi angled his body away, and I surmised he had also been counting.

“And then the audience of all men and boys – there were no females present – let out a resounding shout in unison, “Allahu akbar,” and there was scattered applause. [2]The man with the cane lowered it by his side and he and the other policeman escorted Badawi and back into the van. The audience started moving away and it was as if nothing had happened – this was just part of a normal day for them. And after another three minutes, the van drove away, sirens blaring, and traffic resumed along with people’s normal Friday activities.

“𝑺𝒖𝒄𝒉 𝒂𝒃𝒖𝒔𝒆 𝒐𝒇 𝒂 𝒇𝒆𝒍𝒍𝒐𝒘 𝒉𝒖𝒎𝒂𝒏 𝒘𝒂𝒔 𝒗𝒆𝒓𝒚 𝒔𝒉𝒐𝒄𝒌𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒕𝒐 𝒎𝒆, 𝒚𝒆𝒕 𝒏𝒐𝒃𝒐𝒅𝒚 𝒑𝒓𝒐𝒕𝒆𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒅! 𝑵𝒐𝒕 𝒂 𝒑𝒆𝒓𝒔𝒐𝒏 𝒂𝒓𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒅 𝒎𝒆 𝒔𝒂𝒊𝒅 𝒂𝒏𝒚𝒕𝒉𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒏𝒆𝒈𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒗𝒆 𝒂𝒃𝒐𝒖𝒕 𝒊𝒕. 𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝒆𝒙𝒑𝒆𝒓𝒊𝒆𝒏𝒄𝒆 𝒘𝒂𝒔 𝒆𝒙𝒕𝒓𝒆𝒎𝒆𝒍𝒚 𝒅𝒊𝒔𝒕𝒖𝒓𝒃𝒊𝒏𝒈.”

“In these two photos, you can see there are boys in the front, which was disheartening to me, for this is another generation being exposed to this terrible spectacle and the humiliation of a man. Such abuse of a fellow human was very shocking to me, yet nobody protested! Not a person around me said anything negative about it. The experience was extremely disturbing. In the 2nd image, they’re hitting him, which brings back a lot of memories to me. I honestly have cried a lot about this. I keep a lot inside of me, but just thinking about the mystery of this man prior to and after that moment. So it just really affected me greatly.

“I was only able to take two shots [the scene before and during the flogging]. After everybody had started to leave, I took one additional picture of the area. I found my Saudi friend in the audience and asked him to take a photo of me in front of the mosque. We then walked to his car, after which I made an audio report into my tape recorder while we drove back to my house.

“That evening I reflected upon the instrument of torture, the cane. I went out the next day and went to a souq [market], where I might find a cane such as this. I found there were a lot of them, identical to the one which struck Badawi fifty times. I bought one, brought it home and asked my wife to hit me on the back with it five times and with all her force. I wore a shirt and I thought, oh, this isn’t going to be any problem at all. But she refused to do it. Finally, I pestered her so much with my request that she got angry with me and hit me five times very quickly on the back. I actually suffered, and that night I [looked in a mirror at my back and] noticed pronounced welts. So I was shocked that, even though I was wearing the shirt, that cane did a lot of damage.

“That evening I reflected upon the instrument of torture, the cane. I went out the next day and went to a souq [market], where I might find a cane such as this. I found there were a lot of them, identical to the one which struck Badawi fifty times. I bought one, brought it home and asked my wife to hit me on the back with it five times and with all her force. I wore a shirt and I thought, oh, this isn’t going to be any problem at all. But she refused to do it. Finally, I pestered her so much with my request that she got angry with me and hit me five times very quickly on the back. I actually suffered, and that night I [looked in a mirror at my back and] noticed pronounced welts. So I was shocked that, even though I was wearing the shirt, that cane did a lot of damage.

“I work in human rights now for the State Department. I’m blessed to have meaningful work, even though I work indirectly for the misogynistic, dangerous, and inept Trump. In spite of that, I’m able to do something to help reduce suffering in the world because I emotionally connect with those who are abused. My secondary mission is freedom of expression. So when I read the writings of Raif Badawi, a very intellectual person, [I thought] he’s expressing himself and doing a significant job, but he’s not abusing anybody or the Saudi government. All he was doing was making minor changes and recommendations. In my view, he’s a Saudi patriot! Here’s a Saudi blogger who is expressing himself and he’s in prison just for his thoughts. It’s not just him, it’s thousands of others not only in Saudi Arabia but throughout the world who are being oppressed for expressing themselves.

“As an artist, freedom of expression is extremely important to me. If I lived in China or some country where there’s a very oppressive restriction of expression, I think that I would be in jail or would probably have been killed a long time ago. Because I would be out there with graffiti and spraying [messages]. I would be expressing myself, as I’ve been able to express myself in many ways in the past.”

Côté – “You were risking a lot of things [to be at the flogging].”

Elliott – “Well, I should have mentioned that I was dressed in a thawb, the white outfit [common attire in the Saudi Kingdom and the Gulf states].[3] I wore that so I would blend in. I was also hoping that nobody would see that I had a lighter skin [than most Saudis], that I was obviously a Westerner. I believe I was the only Westerner in this whole audience of approximately 400 people. It was quite a unique opportunity to be there. I didn’t want to be pulled away by somebody or start even worse, they would start attacking me … saying I’m a foreigner or something. So I was nervous. But I also had a personal tape recorder I sometimes use in my State Department work. I turned it on and figured, since I couldn’t do any videotaping, I could at least share [the audio] with my colleagues later on – little realizing the impact it would have on me emotionally. I knew that I had an enormous responsibility to do something with this information, but I had to be very careful.

Elliott – “Well, I should have mentioned that I was dressed in a thawb, the white outfit [common attire in the Saudi Kingdom and the Gulf states].[3] I wore that so I would blend in. I was also hoping that nobody would see that I had a lighter skin [than most Saudis], that I was obviously a Westerner. I believe I was the only Westerner in this whole audience of approximately 400 people. It was quite a unique opportunity to be there. I didn’t want to be pulled away by somebody or start even worse, they would start attacking me … saying I’m a foreigner or something. So I was nervous. But I also had a personal tape recorder I sometimes use in my State Department work. I turned it on and figured, since I couldn’t do any videotaping, I could at least share [the audio] with my colleagues later on – little realizing the impact it would have on me emotionally. I knew that I had an enormous responsibility to do something with this information, but I had to be very careful.

“When I returned to work at the Consulate that Sunday, I informed the Public Affairs Officer that I had been at the flogging. She was shocked and insisted I not reveal my presence on the scene to anyone. I was, however, able to make an official report based solely upon what was by now public information, and subsequently worked on the drafting of an official cable which was sent to Washington.”

“Badawi was scheduled to receive his second of the thousand lashings the following Friday. One of the Consulate Political Affairs officers was to attend this time, but at the last minute the flogging was called off. The Saudi government later said the reason was “on medical grounds,” but I believe it was because the U.S. and some European governments applied diplomatic pressure after the international outcry from the initial lashing.”[4]

Côté – “What is your opinion of Saudi Arabia, having lived there?”

Elliott – “I studied intensively through the State Department about the country [prior to my arrival]. I try not to be judgmental and I’ve lived in other countries in the world. [Saudi Arabia] is a country that, at the foundation, is tribal and very patriarchal. What I couldn’t understand was their perspective of why this type of patriarchy and this type of strict enforcement and strong rule of the royalty was so important. I couldn’t understand it until I started listening to them talk about “how bad the West was.” They like to say, ‘Our country may have strict laws and people may get their hands amputated or their heads decapitated, or like poor Raif Badawi being flogged in public and humiliated…but at least we’re not like the West, where you have all these crimes and women are raped on the streets every day and there’s no morality.’ So they have a lot of [ersatz] reasons to justify patriarchy. It is because of misinformation.

“Even though Saudi Arabia has a huge program for exchanging students with the West. They come back [to Saudi Arabia] and their minds are immediately reabsorbed into a very traditional patriarchal and supreme leadership approach where political and expressive freedoms are derided. The other challenge is young people in institutions of learning are [indirectly] taught very early not to think creatively. There’s no constructive or critical thinking approach. I’ve seen the schools [there] where the teacher stands up in front of 50 or 100 students and the teacher is [like] a lord…giving the information, and the students aren’t allowed to have critical thinking or reasoning. So this is a big problem.

“I’ve seen in other countries that I’ve worked in where the population just doesn’t have that mindset like many do in the West, to question authority. So it’s not something that I [or any outsider] can change. It’s something that has to come from them. The people may someday realize that they’re misinformed about freedom: there’s nothing to fear about it. But it’s going to take many generations, and it might never happen because every time it seems like in these countries there’s an opening, then there’s another countering, such as what happened in Iran [with the 1979 Islamic Revolution].

“Some cultures are able to handle freedom and liberty, but some resist. And I’ve also traveled within China, where I’ve seen a similar thing. The Chinese are very proud, and they point with ridicule about how the West and democratic countries are not doing well, that they’re weak, and they have no vision and they only think about next day. So it’s all a matter of your perspective. I really try not to be judgmental, but when I see an animal or a person suffering at that moment, you can’t help but have sympathy and empathy. You can’t help and want to run and stop and [restrain] the hand of that person dispensing this abuse. It’s just impossible to watch cruelty without having your heart involved.”

Côté – “As a Westerner, what do you think about the behavior from Western governments? On one side, they can be critics of Saudi Arabia, but on the other hand, they are selling [arms]. They are trading with them, and they consider them strategic ally, very important. Can the West help to change things in Saudi Arabia to bring more freedom there?”

Elliott – “The West has a huge obligation. [In fact,] all people around the world have a huge obligation, to reduce violence. The problem is that [everyone is] seduced by commercialism and marketing. They’re seduced by one of the oldest malignant powers [mentioned] in all of the ancient scriptures, which is money and wealth … [which they] don’t want to share. [Or] they only want to share it with people who look like them or act like them. And this is a very small minded but very commonplace mentality, and it’s common in all animals, in most species.

“The root of many problems is that … [many] people are not capable of … a higher level of consciousness. That’s just the way our species is. And so, because of that – and there’s such a massive number of them, unfortunately – the world is pulled down. And whether or not a free society can influence another society to be freer, it depends on a lot of things. The biggest setback when [Westerners] try and influence other countries is when we do it by threats or by trickery; or we set a poor example; or we’re, out of ignorance, downright insulting.

“We don’t understand [other] cultures. We don’t spend time learning about how to be friends with them. We’re judgmental, and we come across as if we know everything. This very patronizing approach offends other nationals. When I was [working] in Saudi Arabia, one way that I learned to really connect with the people there was just to spend a lot of time and to get to know them, and slowly they would feel comfortable to reveal a little bit more about their life and opinions. Then they’re interested in hearing about issues such as press freedom–at that point. They’re interested in hearing about democratic values. But if you just go there and you show them Hollywood pictures and say you need to be more like me, of course they’re going to run in the other direction. Of course, they’re going to become more entrenched and … more justified at their actions. So the problem with North Americans and a lot of people in the West, frankly, is that they just don’t understand how to connect with other cultures.”

Côté – “[So] is [Badawi] a hero [to Saudis], or [in their eyes] somebody that should be punished?”

“𝑰𝒕’𝒔 𝒉𝒂𝒓𝒅 𝒕𝒐 𝒅𝒆𝒄𝒊𝒑𝒉𝒆𝒓 𝒘𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒚’𝒓𝒆 𝒕𝒉𝒊𝒏𝒌𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒃𝒆𝒄𝒂𝒖𝒔𝒆 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒚’𝒗𝒆 𝒈𝒐𝒕 𝒕𝒉𝒊𝒔 𝒘𝒉𝒐𝒍𝒆 𝒂𝒓𝒎𝒐𝒓 𝒐𝒇 𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒍𝒊𝒕𝒚 𝒕𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒚 𝒎𝒖𝒔𝒕 𝒎𝒂𝒊𝒏𝒕𝒂𝒊𝒏 𝒊𝒏 𝒐𝒓𝒅𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒐 𝒅𝒆𝒂𝒍 𝒘𝒊𝒕𝒉 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒊𝒓 𝒄𝒖𝒍𝒕𝒖𝒓𝒆 𝒂𝒏𝒅 𝒃𝒆 𝒄𝒐𝒏𝒏𝒆𝒄𝒕𝒆𝒅 𝒕𝒐 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒊𝒓 𝒇𝒂𝒎𝒊𝒍𝒚 𝒂𝒏𝒅 𝒇𝒓𝒊𝒆𝒏𝒅𝒔.”

Elliott – “The way somebody who is controversial is [understood] by the people from a country which is punishing that person is somewhat inscrutable. It’s hard to decipher what the Saudis there were thinking, because they’ve got this whole armor of cultural reality that they must maintain in order to deal with their lives and be connected to their family and friends. I found very few Saudis who were daring to communicate information or values contrary to the Saudi monarchy – whether through art or words. There were some who have been able to do that, but [then] they had to flee the country or face punishments, as Raif Badawi has.

“Women’s rights is another point: I found that women want more freedom…that many of them don’t want to wear this restrictive head covering. They don’t want their adolescent girls to be forced to wear [abaya and hijab] and have to suffer by not being able to get out in the sun or play sports. But expressing such concerns is very rare. The entire family structure, society, and the patriarchal culture enforce that limited movement for females.

“A fascinating thing I discovered about Saudis is that they consider themselves to experience less ‘crime’. For example, something like this [flogging]; many don’t consider this a crime. They consider this reinforcement of the Qur’an, and it is Qur’anic. This is, to most Saudis, a punishment supported by their holy words. So what people consider a crime is at question. In Saudi society, according to well-established independent and external sources, women are abused frequently or are victims of rapes by intimate partners, but it’s rarely reported domestically. Because if a woman or a girl reports this, then she’s considered a dishonor to the family and has no future. She might lose friends or contact with family [after reporting]; she might even be killed; she might be accused of being prostituted. Child abuse is another crime. Now that we have video on the social media such as YouTube, you can see, if you type in Saudi molestation, videos of men attacking children in the stairwells or in elevators, recorded on the CCTV cameras. So, except for rare cases published in external media, we have no idea of the suffering, because the reporting is so restricted. We actually have no idea of the extent of horrors that go on behind the scenes.

“Ironically, Google daily data clearly demonstrate that the greatest number of searches for pornography by keywords is from the Middle East, which has very restrictive cultures. We have statistical evidence of this, and it seems to be a byproduct of the repressive societies.

“But, just as one cannot legislate morality, one can’t force a culture to change and transform; it is best done through positive role modeling and very delicately…with positive ideas and messages. When I was serving [in Saudi Arabia], in public-facing media, I always tried to accent the positive things: beautiful architecture, beautiful mosques, their artwork. This is how to create cultural bridges and actually effect positive change”

Hear the Audio File

highlights from the transcript: 00:00 Ambient sound as people assemble in front of the mosque. 01:15 Warning by police to not record or photograph anything. 02:00 Attendees in my vicinity making small talk about the event. 03:40 Whipping of Raif Badawi commences. Striking sounds are heard 50 times. 04:05 Whipping ends. Shouts of "Allahu akbar!" from the crowd. 04:10 A local Saudi friend comes up to me and I acknowledge him. 04:50 Sounds of police cars departing for next minute. 05:45 My friend tells me where he parked his car and I walk there with him. 06:40 He says about police, "Don't let them see you" as I take a photo of the mosque. 08:20 As we walk to his car, I inform my friend more about Mr. Badawi. 08:40 Police transport Mr. Badawi away in a van (I describe it as a Nissan van with blue striping. 10:10 As we walk to his car, my friend discusses another flogging he witnessed. 10:45 I relate the plan for more floggings, per the Saudi court order. 11:05 We pass the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 11:15 I express relief that no police saw me photograph. 11:30 My friend mentions seeing another person at the flogging who tried to take a photo and his mobile camera was confiscated. 12:00 My friend exclaims that I look like a Pakistani because I had dressed accordingly to blend in. 12:25 We arrive to my friend's car. 13:35 I mention to my friend, "I came prepared, in case they took me to jail". 14:05 I mention how I had to pray with the others outside of the mosque prior to the flogging. 14:45 I ask my friend to take me by the mosque so I can get a better photo from the car window.

0 Comments