People sometimes look at photographers as thieves. We sneak up on the unsuspected and, sometimes without permission, do something that requires the verb “to take”. When we take a photo, we seem to steal a moment, a parsec which may or may not be an accurate rendition of reality. Where we position ourselves determines how the light will fall on the subject, their angle of dominance or submissiveness, fame or folly.

This act of taking is painless, and, if we have permission – such as in portrait photography – the process is usually pleasant and the results gratifying to the subject. But in my experience, there is always this feeling of knowing more than the subject for some time exactly what we have captured. The photographer is therefore a visionary, even a mystic. It’s understandable that some people resent or fear the photographer.

Photographers are also perceived as sneaky. We’re always looking, searching, and even without the camera we’re snapping infinite mental images everywhere we go. We see things that surprise or delight us; but we also see (and unfortunately can recall) terrible and horrifying things – which we would prefer to forget, yet cannot. Perhaps it is this mysterious vision which provokes many indigenous cultures to forbid the taking of photos, lest we “steal a soul” (babies being the most vulnerable subject).

The sociologist Susan Sontag wrote in her acclaimed book, 𝘖𝘯 𝘗𝘩𝘰𝘵𝘰𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘩𝘺 (1976), “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge –– and, therefore, like power.” Recognizing this power means knowing the potential for concern, even fear, on the part of a subject.

But there is an ethical dimension to consider. To be an ethical photographer one would assume we ask a subject for their permission to take or use their photo, or a photo of their family, home, or certainly something private and precious. But there’s the rub: the interruption from the very act of asking usually destroys the very uniqueness of the photograph. This is where the waiting process comes into play. When I arrive to a scene I think has potential, I may spend a lot of time getting myself and my subjects comfortable with my presence. This could take a few minutes…or hours; I have experienced the spectrum within these extremes. Often, I will engage my subjects in light banter and initially not showcase my camera. The ethical photographer must be prepared for rejection. Learning and using the local language and dialect is essential – even if it’s just a few sentences. Smiles and a positive tone are likewise essential. There’s a 𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘥 𝘱𝘳𝘰 𝘲𝘶𝘰. Most people are no different than creatures of the wild, and prefer an interloper to assume a deferential posture, which I also always adopt.

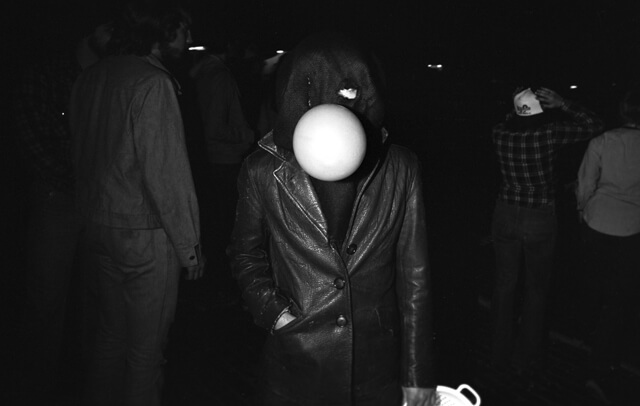

And then there are public scenes or subjects for which there is no introduction, sometimes involving a telephoto lens. I sometimes make these photos as part of my visual journaling, but, to me, they are not fine art; these are documentary or photojournalistic photos, no matter how finely crafted. After I took this photo of a woman with a baby in the street, should I have run a block toward her to tell her what I did, or ask her permission retroactively? In cases such as these, it seems better to move along and not confuse or frighten anyone!

And then there are public scenes or subjects for which there is no introduction, sometimes involving a telephoto lens. I sometimes make these photos as part of my visual journaling, but, to me, they are not fine art; these are documentary or photojournalistic photos, no matter how finely crafted. After I took this photo of a woman with a baby in the street, should I have run a block toward her to tell her what I did, or ask her permission retroactively? In cases such as these, it seems better to move along and not confuse or frighten anyone!

A serious photographer is always aware of what we are doing, how we do it, and how the concept of “taking” dictates how we might be perceived – what Sontag defined in her seminal work as the “incriminating” nature of a photograph. A conscientious photographer strives to improve a situation, by communicating the value of their efforts. This does not mean we must take photos exclusively of people or scenes that are “attractive”. But the 𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯-𝘥𝘦-𝘦̂𝘵𝘳𝘦 of an image should be a positive one. So when I photograph an impoverished laborer, a public melee, a dingy façade or weirdly cluttered space, I desire to show that even these can be evaluated and favorably esteemed. How successful I am in this process determines my personal satisfaction.

I believe the success is also evident to the viewer. Am I “taking” photos? I prefer to think of “giving” photos. I give of my physical labor and sacrifices, my time, my craft, my years of study of related aesthetics, tools, techniques, light, cultures, and communications. I give in my careful selection of subjects great and small, so that others may see, comprehend, and appreciate. I view myself as a photographer, but not a thief.

Terrific article. Love your deep thoughts and sensitivity and quoting the great Susan Sontag. The pic of the mother carrying the child is excellent. You are a great writer.

Thank you Mo! Yours is the first comment in my new Blog section.